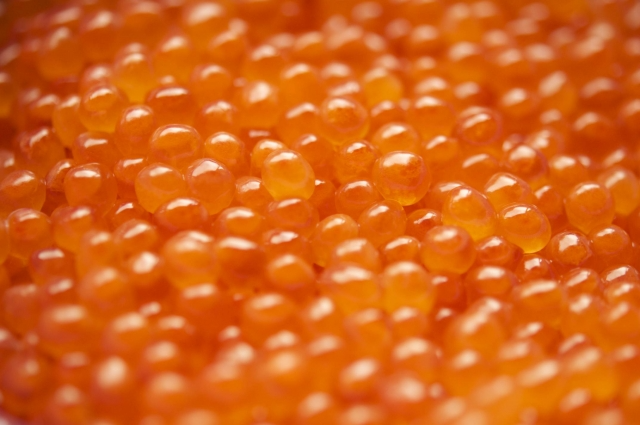

Among visitors to Japan, fascination with sushi and fresh seafood grows every year. Particularly, "ikura" (salmon roe) enchants many with its dazzling, jewel-like appearance and uniquely delightful texture.

Imagine popping bursts of flavor, a gentle sea aroma unfolding on your palate, and radiant, glossy spheres that look too beautiful to eat. Ikura truly stands as one of the shining symbols of Japanese culinary artistry.

In this article, we'll explore ikura in depth—the basics, how it differs from its overseas counterparts, its seasonal highlights and top production areas, and the rich cultural traditions around it. If you're planning a trip to Japan, this guide will help you not only savor ikura but also appreciate its story and craft, turning your tasting into a memorable cultural experience.

1. What is Ikura?

Ikura is a beloved traditional Japanese delicacy made by marinating fresh salmon eggs in salt or soy sauce. Each translucent, reddish-orange bead bursts with a satisfying pop and melts smoothly in your mouth, revealing the ocean’s essence.

Interestingly, the word “ikura” originates from the Russian “икра (ikra),” meaning fish eggs in general. But in Japan, ikura specifically denotes salmon roe—making it a distinctly Japanese treasure.

There are two popular ways ikura is prepared: “shio ikura,” simply salted, and the more common “shoyu-zuke ikura,” marinated with soy sauce. The latter is a flavor staple in dishes like sushi and rice bowls that you simply can’t miss.

Usually served chilled, ikura perfectly complements rice and other seafood, forming the centerpiece of iconic Japanese dishes such as seafood rice bowls (ikura-don), gunkan sushi, and hand rolls.

2. Types of Ikura in Japan

While ikura may appear uniform at first glance, subtle differences in grain size, flavor, and texture come from the type of salmon they come from. Here are some popular varieties you might encounter in Japan:

White Salmon (Shirozake) Ikura

- Japan’s most common ikura

- Large, popping grains

- Rich, savory flavor, often used with soy sauce or salt

- Classic topping for sushi and rice bowls

Silver Salmon (Ginzake) Ikura

- Farm-raised and widely available

- Smaller, softer grains

- Mild flavor with little pungency

- Affordable and great for casual home dining

Sockeye Salmon (Benizake) Ikura

- Usually imported from Alaska

- Smaller grains with rich, deep flavor

- Occasionally featured at upscale restaurants

Trout (Masu) Ikura (Masuko)

- Small grains with soft membranes

- Light, easy-to-enjoy taste

- Common in supermarkets and hand-rolled sushi

Golden Ikura

- Rare, naturally golden-hued ikura

- Small grains with a refined flavor

- Often served in high-end dining and prized as gifts

3. Japanese Ikura vs. Overseas Ikura: What Makes It Special?

What sets Japanese ikura apart from versions found overseas—in places like the U.S. and Russia? Let’s dive in:

Processing and Seasoning Styles

In Japan, freshness takes center stage. Ikura is lightly salted or marinated in soy sauce to highlight its natural, oceanic sweetness. Regions like Hokkaido and Tohoku cherish this simple yet elegant seasoning.

Conversely, ikura abroad often undergoes heavier salting to extend shelf life. This results in a saltier bite, and it’s traditionally enjoyed atop breads or crackers.

Size, Texture, and Freshness

Japanese ikura is known for its large, translucent pearls that pop delightfully in your mouth, thanks to strict freshness and quality controls.

Meanwhile, overseas ikura tends to have smaller grains and sometimes a sticky texture. Often frozen or canned for transport, it can lack the freshness and vibrant flavor found in Japan.

How It’s Enjoyed Culturally

In Japan, ikura crowns sushi and seafood bowls and is a staple during celebratory times like New Year. It’s woven deeply into Japan’s culinary fabric.

Overseas, ikura’s role is more as an elegant appetizer on canapés or atop crackers with butter—part of Western dining culture.

4. Where to Find the Finest Ikura in Japan

Japan’s ikura production thrives along the Pacific coasts of Hokkaido and the Tohoku region. The more salmon run in these areas, the better the ikura quality.

Hokkaido

Japan’s top producer of ikura, where autumn brings salmon upstream along its shores. Eastern Hokkaido, including Kushiro, Nemuro, and Shibetsu, is famed for large, exquisite ikura grains.

Local fisheries and processors meticulously preserve freshness before shipping nationwide. Don’t miss tasting ikura don at restaurants here—an unforgettable treat for travelers.

Iwate Prefecture

Along the scenic Sanriku Coast in Tohoku, Iwate boasts rich salmon catches and high-quality ikura. Home-style soy sauce-marinated ikura is a cherished local specialty, showcased in market stalls during season.

Miyagi Prefecture

Places like Kesennuma and Ishinomaki offer plentiful salmon fisheries and excellent ikura. The region’s seafood bounty makes it a beloved destination for fresh ikura dishes at accessible prices.

5. Best Time to Taste Ikura in Japan

The peak ikura season coincides with the salmon spawning period, from September through November, when coastal markets brim with fresh “sujiko” (roe sacs).

During this vibrant season, ikura features large, luminous grains with firm membranes that offer a delightful pop. Soy sauce seasoning brings out its savory umami, capturing the essence of autumn in Japan.

If you visit fishing towns then, you'll spot lively signs advertising ikura don at local eateries, bustling with locals and travelers alike eager to savor the freshest flavors.

6. Must-Try Ways to Enjoy Ikura

While ikura is delicious solo, Japan offers a variety of mouthwatering ways to experience it. Here are favorites to try on your trip:

Ikura Don (Rice Bowl)

For the ultimate ikura experience, dive into an ikura don. Picture a generous mound of bright ikura atop warm, fluffy rice, garnished with crisp seaweed and refreshing shiso leaves. In Hokkaido, you might even find indulgent combinations like uni and ikura don—a seafood lover’s dream.

The warmth of the rice gently releases the ikura’s aroma and umami, creating a harmony that’s simply unforgettable.

Ikura Sushi (Gunkan Maki)

Found on conveyor belt sushi bars and in elegant sushi restaurants alike, gunkan maki topped with ikura is a must-try. Bite-sized and flattering to both eyes and palate, the seaweed-wrapped vinegared rice cup brimming with bright salmon roe is beloved by locals and visitors worldwide.

Onigiri (Rice Balls)

For a quick, portable snack, try ikura onigiri from convenience stores or supermarkets. Simple yet packed with ikura’s vibrant flavor, it’s perfect for exploring Japan while enjoying authentic tastes.

Appetizers and Canapés

Ikura also shines beyond traditional Japanese dishes. Placed atop crackers or paired with cream cheese, ikura can elevate any party or celebration with its vibrant color and unique flavor.

7. Ikura’s Special Role in Japanese Culture

Ikura is more than a tasty treat—it’s woven into the fabric of Japan’s cultural celebrations, especially "haredays," or festive occasions.

New Year’s Osechi Cuisine

Every New Year, ikura graces osechi boxes as one of the celebratory side dishes. Its auspicious red hue and multitude of round grains symbolize prosperity and flourishing descendants—a perfect gesture of good fortune.

Weddings and Celebrations

With its luxurious appearance and festive feel, ikura frequently adorns kaiseki meals and banquet appetizers, adding stunning color and flavor to chirashi sushi and more.

Home Cooking Favorite

While considered a luxurious ingredient, many Japanese families enjoy ikura at home, especially in autumn when marketplaces overflow with fresh sujiko ready to be marinated.

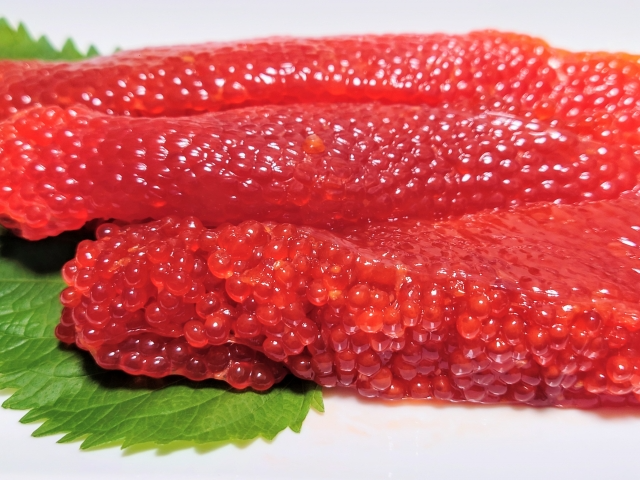

8. Sujiko: Ikura’s Cousin

Sujiko looks much like ikura at a glance—both are salmon eggs with vivid reddish-orange colors—but for first-timers, understanding their differences enriches your tasting adventure.

What is Sujiko?

Sujiko is salmon or trout roe still held together inside their membranous sac, unlike ikura which is separated into individual eggs.

In Japan, sliced and marinated sujiko is popular as a home-style delicacy in some regions, often salt- or soy-sauce flavored.

Visual Differences

Ikura's plump, translucent eggs hold their shape, glowing with a bright, jewel-like luster. Sujiko’s eggs appear darker red, often flattened together by their membranes, and are sold as whole or partial sacs.

Taste and Texture

Ikura delights with individual popping grains, while sujiko offers a stickier, firmer bite due to the membranes. Sujiko usually carries a stronger, saltier flavor and sometimes a fermented umami from aging.

Eating Style

- Ikura is typically enjoyed directly on rice, sushi, or as a garnish.

- Sujiko is often sliced thinly and eaten as onigiri fillings or rice accompaniments, especially in the Tohoku region where it’s a homemade tradition.

Sujiko’s higher salt content aids preservation, making it a practical and somewhat more affordable alternative to ikura.

Myth Buster

A common misconception: breaking up sujiko turns it into ikura. In reality, they differ by processing methods and the egg maturity selected, resulting in distinct textures and flavor profiles.

In Conclusion

Japanese ikura offers a captivating experience, shining in taste, appearance, and cultural significance. When you visit Japan, keep these tips in mind to fully enjoy:

- Seek freshness—plan your trip during the peak season, September through November, focusing on Hokkaido and Tohoku for top-quality ikura.

- Explore different ways to savor it: ikura don, gunkan sushi, elegant canapés, and more.

- Immerse yourself in ikura’s cultural stories and the festive occasions it graces.

- Notice how Japanese ikura’s gentle seasoning and delicate texture distinguish it from overseas versions.

More than just a sushi topping, ikura invites you to taste Japan’s seasonal rhythms and cultural richness. Don't miss the chance to delight your senses and deepen your journey through Japanese cuisine—you’ll leave with vivid memories and new favorites to treasure.

Search Restaurants by Popular Cuisines

Search Restaurants by Characteristics